CONSULTATION PREMISE #4: A faithful Christianity in a darkening New Future demands more than redoubled efforts at virtue. It demands interrogation of tenets inherited from the world of the Old Future. If the positive declaration of “This” is to be meaningful, it must now be accompanied by the negative “Not That.”

By John Elwood

There has been in Christian history a thin tradition which tried to proclaim the possibility of hope without shutting its eyes to the data of despair, a tradition which indeed insisted that authentic hope comes into view only in the midst of apparent hopelessness…. This is, we must emphasize, a thin tradition. – Douglas John Hall [o]

Is Christianity ready for the “New Future” of ecosystem failure and societal upheaval?

I am not asking, “Are Christians ready?” For the most part, we already know the answer to that question. Christian climate practitioners are intimately familiar with the prevalent un-readiness of Christians in the face of the planetary crisis. And there is no shortage of diagnoses of our problem. They generally follow a pattern something like this:

Many of us regrettably believe that science is the enemy of faith. Furthermore, we maintain that “this world is not our home,” that we are only passing through, and that the material world has no eternal significance. With this unfortunate framing of the natural realm, many Christians are highly susceptible to heaven-focused dualism—that what really matters is some other world in which we will spend eternity. And worse (this line of reasoning goes), unrelated social causes—abortion, desegregation, feminism, the Equal Rights Amendment, and changing cultural norms around gender and sexuality, among others—have driven many Christians into political alliances with polluters and anti-regulation marketeers. Add to these a listing of unpleasant modern Christian habits—flirtation with the prosperity gospel, blind loyalty to extractive capitalism, and unquestioning veneration of famous preachers—and you have a faith community particularly vulnerable to misinformation peddled by the extractive industries and climate denialists.

Virtually all such assessments offer at least one common solution: Christians need to learn their Bibles, or a truer version of Christianity. Katharine Hayhoe, undeniably the most effective American Christian climate science communicator, recently crystallized this perspective: “I really believe that if we took the Bible seriously, if we actually knew what it said . . . that we would be at the front of the line demanding climate action because it is all through the Bible.”[i] And Christian environmental leader Kyle Meyaard-Schaap has summarized the Bible as “the Big Story of God’s love for all of creation, our responsibility toward it, and the good plans God has for it” – a sadly unrecognized story, however, to many or most Christians. [ii]

Faced with this assessment, many Christians find themselves in a difficult spot. Their faith tradition is presumably spot-on; they themselves, however, are a bit of a problem. In survey after survey, they find that their faith communities are the least likely to take the ecosystem crisis seriously or to acknowledge it at all.[iii] The answers, they are told, are all there in their Bibles, if they would only pay attention. Problematically, however, religiously unaffiliated people—the “nones”—who never pore over the Bible for their environmental stances, exceed them by wide margins in matters of concern for the earth.[iv] Worse yet, those same “nones” often profess much higher levels of concern for justice in the non-environmental realm, including immigration, structural racism, and Christian nationalism.[v] This cannot be smoothed over: American Christians tend to profess less concern than biblically illiterate secularists on key environmental and social matters. Is it possibly more than just our failure to understand the Bible?

But What About Christianity Itself?

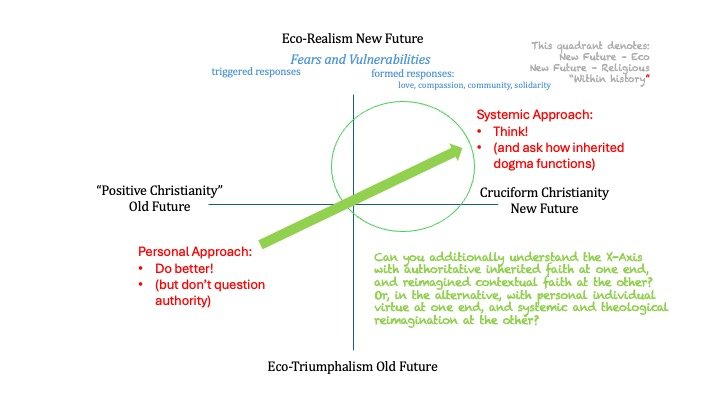

It's unfortunately easy to criticize Christians in the environmental sphere. But we started with a question about Christianity, not Christians. “Is Christianity ready for the ‘New Future’ of ecosystem failure and societal trauma?” What if the problem is within Christianity itself, in its dominant historical and contemporary streams? What if Christianity—not just its imperfect followers—is not ready for the future for which we must now prepare? In Consultation Paper #2, I suggested that Positive Christianity—a theological frame that foregrounds themes of eschatological victory, certitude, and expectation of happy endings—has swept the field of Western church spirituality, soundly defeating Cruciform Christianity, which foregrounds God’s solidarity and immanence amidst earthly suffering. Christus Dolor (the suffering Christ) has hardly ever been a match for Christus Victor in the spiritual imagination of the dominant North Atlantic churches.

And yet, we must now ask: What does this positive, confident, triumphal Christ possibly have to say to a world beset by suffering and hopelessness? Perhaps the historical record may offer some clues.

The Christian church knows all about traumatic climate shocks. The faith arose during the hospitable Roman Climate Optimum, witnessed the collapse of empire when the Mediterranean warmth succumbed to the Antique Little Ice Age, suffered through the frigid and brutal General Crisis of the 17th century, and struggled through repeated climate shocks under the pallid sun of the Little Ice Age. Historians only recently began to correlate sudden climate changes with societal trauma, but the pattern is already becoming clear: episodes of rapid climatic changes have generally been accompanied by crop failures and famine, plagues and natural disasters.[vi] According to historian Philip Jenkins, “such eras are richly productive of wars and rebellions, of demographic crises and hunger riots, of pogroms and witchcraft panics, and of apocalyptic and millenarian outbreaks.”[vii] These were times of starvation and mass mortality, when the dying sometimes outnumbered the living, when the metaphor of the Horsemen of the Apocalypse was particularly resonant. Famine, Plague, and Death devastated societies, and they rarely rode abroad without the company of the fourth rider: War. Jenkins observed that traumatized and hungry people “framed their suffering according to whatever ideologies lay close at hand,” especially their religion. And the Abrahamic religions embraced providential worldviews: the affairs of earth being controlled by God, with human conduct attracting God’s favor or wrath. In such times, God was clearly angry, and it was tempting to believe that infidels on the frontiers or amongst us were the reason why. It is not difficult to see why the frigid 17th century was also notable for its murderous religious wars and massacres of religious minorities.[viii]

Christian environmentalists today would do well to ask: How did the religion of Christus Victor handle past climatic upheavals? Is the triumphal Christ of Positive Christianity the one to lead us into the hunger, hopelessness and conflict of the New Future? These questions are framed in the abstract, because we can hardly anticipate the specifics of unavoidable trauma in a failing global ecosystem. But specific dangers must not be ignored. Many of these dangers lurk along the tenth parallel north, the circle of latitude running from Senegal to Somalia in Africa, and on through Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. These lands and communities are among the most vulnerable to the ravages of climate change—and also where Christianity and Islam compete for converts, dwindling resources and political dominion. In Africa, almost one billion Christians and Muslims eye each other across this frontier; in Asia, nearly 400 million.[ix] Both religions are flourishing in these regions, but in increasingly conversionist, triumphalist, millenarian and fundamentalist forms, as is common in times of climate shocks.[x] How, we must ask, will these religions function in the face of today’s “horsemen”—advancing deserts, unpredictable cycles of flooding and drought, rising seas, and extreme weather events?

Listening to Alternative Voices

If it’s true that Positive Christianity is becoming increasingly unintelligible in our context, Christians in the West may have to look beyond the horizon for alternatives. One important set of voices comes from Japan. Protestant theologian Kosuke Koyama argues that Western Christianity has lost the ability to find hope in the broken Christ of the cross: “A strong Western civilization and the 'weak' Christ cannot be reconciled harmoniously. Christ must become ‘strong.’ A strong United States and a strong Christ!”[xi] Kanzo Uchimura, founder of the Japanese Nonchurch Movement, observed that Westerners “love to fight…. So when they adopted Christianity, they made it a fighting religion, a European and American religion, entirely contrary to its original genius.”[xii]

And Japanese theologian Kazō Kitamori proposed a theology of “the pain of God.” While Western cultures embrace triumph and progress, he argued, the deepest impulse of the Japanese mind is expressed as tsurasa, the tragic literary narrative of one who suffers concealed agony and dies for others.[xiii] For Kitamori, the Japanese heart is not moved by the glory and power of Christus victor, but only by the fellow-suffering of Christus dolor.

The point for us, however, is not the cultural difference between Japanese tsurasa and Western triumphalism, but the spiritual difference between historical Christian optimism and a yet-unknown Christian spirituality that is intelligible in the world of ecological crisis. What kind of Christianity can speak to those looking into the abyss of the ecosystem crisis, without drawing them away from this world that God loves?

What Must We Rethink for Our Context?

Many Christian environmental thinkers address this conundrum by addition, expanding their inherited religious narratives to make room for earth-care—effectively building onto the edifice of optimistic Positive Christianity a garage apartment or finished basement for a recently-arrived guest. The problem, however, is that the prophetic call of “creation care” is often in tension with the inherited doctrines of the original structure. We tell ourselves: love and serve this world (even though our real homeland is in another); labor to minimize the global crisis (even though God is in control of history); stand in solidarity with the non-human biosphere (even though humans alone bear the image of God); make common cause with all peoples (even though they must ultimately abandon their beliefs and adopt ours); defend the sanctity of every living person or thing (even though our religious tribe has been uniquely chosen to receive God’s saving grace)—and so on. The heavy lifting, however, begins only when we interrogate the dogmas that breed resistance to our ethical imperatives.

This, perhaps, is why Canadian theologian Douglas John Hall insists upon negation. The Theology of the Cross—broadly similar to “our” Cruciform Christianity—can only be understood as a negation of the triumphalist Theology of Glory. In seeking to rediscover a long-neglected “thin tradition” within Christianity, we must contrast it with what it stands against: the dominant tradition of Positive Christianity. If “this” is to be meaningful, it must be “not that.”

In distinguishing between Positive and Cruciform Christianity, Hall’s theology would foreground a series of “this-not-that” principles with which we might begin to grapple. Some of these Hall would propose as outright binaries: embrace “this” and reject “that.” For our purposes, however, we are exploring what to foreground, to prioritize; and what must now be deemphasized as the once-dominant themes of our tradition. It would be far more comfortable to state only the affirmations; but in so doing, we would leave untouched the corpus of Christian theology that hampers our engagement with a world of unavoidable trauma. In preparing for the “New Future,” therefore, a Cruciform Christianity might choose to prioritize:

Divine solidarity with suffering—not—triumph over evil.

Willingness to bear the cross of suffering—not—expectation of victory.

Christ, the weakness of God—not—Christ, the Omnipotent Lord.

Openness to challenge and criticism—not—conversionist promotionalism.

Welcoming curiosity and dialogue—not—asserting exceptionalism and authority.

Theological modesty and humility—not—claims to ultimacy.

Theological understanding in process—not—theological finality.

Focus on this world—not—focus on a secondary world.

Solidarity with the creation—not—rising above the creation.

Focus on Christ immanent—not—focus on Christ transcendent.

Christ’s first coming—not—Christ’s second coming.

Acceptance of human limits and earthly belonging—not—human mastery.

Embracing common ground—not—exclusive and exceptional.

Following Christ into the darkness—not—seeking God to banish the darkness.

Allied with the greater community—not—competitive and conflictual.

The cross as compassion and solidarity—not—rescue from finitude.

Disestablishment from the dominant culture—not—growth and cultural power.[xiv]

Surely there’s something in this list to horrify nearly every faithful follower of dominant Christian traditions. But as we seek to reimagine a faith that is intelligible in a world of unavoidable trauma, one that foregrounds solidarity with a world of suffering, and one that resists the violence and barbarism that accompany times of abrupt climatic disruptions, might we be willing to put some of our inherited baggage on the table? When we do so, we are acknowledging that beliefs don’t just sit there, being true or false; they function. How, we must now ask with eyes wide open, have they functioned in the Christianity of our time? What must we now be willing to deemphasize? And what must we take up in their place?

This is the challenge of reimagined faith in the New Future. I am honored to be imagining it together with you.

Grace and peace,

John

NEXT STEPS

Explore the thought of Douglas John Hall for yourself. (See Recommended Reading/Listening below.)

Within the next few days, you will receive a follow-up newsletter that includes two responses to John’s essay, one from Lowell and one from a pioneer in eco-realistic ministry from the UK, our friends at Borrowed Time. A mechanism will be provided for you too to weigh in, as you wish.

This is the last of the four premises, and the last of the four papers, to send you before our July 26 in-person consultation. Stay tuned in the beginning of July for some synthesizing and preparatory comments, for registrants and non-attendees alike.

Registration remains open for our in-person Consultation: Friday, July 26, 2024, 9 AM- 4PM, at Catholic University in Washington, DC. Cost is $75. The American Scientific Affiliation is graciously administering our registration here. NOTE: lodging is only available Thursday and/or Friday night for those registering for the entire ASA Conference, which is a separate registration. (See below).

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation for the Consultation through our fiscal agent, William Carey International University. Thank you. Donate here.

Recommended Pre-Consultation Reading for June

The writings of Douglas John Hall, Canada’s greatest living theologian, energize much of the theological exploration in these papers, particularly in his critique of the “theologies of glory” and the North Atlantic culture that that has been nurtured by them.

For an accessible summary of Hall’s treatment of the “theology of the cross,” we would recommend The Cross in Our Context: Jesus and the Suffering World. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003.

The 20-page 1st chapter provides an eloquent summary of the theology of the cross. Hall writes:

“Doctrine has always to be submitted to the test of life. Doctrine must serve life, not life doctrine. Like the Sabbath, Christian theology was and is made for humankind, not humankind for theology. So, if in order to hold onto doctrine I have to lie about life, or repress what is actually happening to me and my world, then doctrine is functioning falsely. . . . It is easy enough to devise theories in which everything has been “finished”—all sins forgiven, all evils banished, death itself victoriously overcome. But to believe such theories one has to pay a high price: the price of substituting credulity for faith, doctrine for truth, ideology for thought.”

However convincing this may have been when the volume was published in 2003, it speaks with devastating clarity into the age of eco-realism.

As a shorter alternative to this book, Hall was interviewed by Tripp Fuller on the Homebrewed Theology podcast, discussing two others of his books, both of which have also made important contributions to our reimagination of theology in the New Future. https://trippfuller.com/2020/01/16/douglas-john-hall-what-christianity-is-not-a-theology-of-the-cross/. In it, Hall says:

“The purpose of faith is to give us a certain amount of confidence, not certitude, but confidence that we can enter as deeply as possible into the negativities that we ourselves feel. I always say to my students, “What must you suppress in order to believe what you believe as Christians? What must you repress and suppress?” And the answer should be, the one you should strive for is: nothing. There is nothing I have to lie about in order to believe what I believe. That’s the Theology of the Cross.” (37:30)

[0] Hall, Douglas John. Lighten Our Darkness: Toward an Indigenous Theology of the Cross. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976, 113.

[i] BTS Center: Collective Honesty and Complicated Hope webinar; https://vimeo.com/949594112/3343965abe; accessed 5/29/24.

[ii] Meyaard-Schaap, Kyle. Following Jesus in a Warming World: A Christian Call to Climate Action. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2023, 60.

[iii] Clements, John M., Chenyang Xiao, and Aaron M. McCright. “An Examination of the ‘Greening of Christianity’ Thesis Among Americans, 1993–2010.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53, no. 2 (2014): 373–91, finding no evidence of “greening” of Christianity; Arbuckle, Matthew B., and David M. Konisky. “The Role of Religion in Environmental Attitudes.” Social Science Quarterly96, no. 5 (2015): 1244–63, finding that members of Judeo-Christian traditions are less concerned about environmental protection than their nonreligious peers, and that religiosity somewhat intensifies these relationships for evangelical Protestants, Catholics, and mainline Protestants; Konisky, David. “The Greening of Christianity? A Study of Environmental Attitudes Over Time.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY, November 14, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3092262, finding that Christian environmental attitudes have regressed over recent decades; Smith, N., and A. Leiserowitz. “American Evangelicals and Global Warming.” Global Environmental Change 23, no. 5 (October 1, 2013): 1009–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.04.001, finding that evangelicals accept the reality of global warming and its human causes at far lower rates than the general public; Funk, Cary. “Religion and Views on Climate and Energy Issues” Pew Research Center Science & Society (blog), October 22, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2015/10/22/religion-and-views-on-climate-and-energy-issues/, finding that white evangelicals are the least likely grouping to accept human causes of climate change; “Believers, Sympathizers, and Skeptics: Why Americans Are Conflicted about Climate Change, Environmental Policy, and Science.” (2014) Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.prri.org/research/believers-sympathizers-skeptics-americans-conflicted-climate-change-environmental-policy-science/, finding that White evangelicals express the lowest concern regarding climate change, followed by White mainline Protestants; and PRRI | At the intersection of religion, values, and public life. “The Faith Factor in Climate Change: How Religion Impacts American Attitudes on Climate and Environmental Policy | PRRI,” October 4, 2023. https://www.prri.org/research/the-faith-factor-in-climate-change-how-religion-impacts-american-attitudes-on-climate-and-environmental-policy/, finding that from 2014 to 2023, the percentage of white evangelicals who accept that climate change is caused by human activity has fallen from a one-time low of 14% to last-place 8% at present.

[iv] PRRI | At the intersection of religion, values, and public life. “The Faith Factor in Climate Change: How Religion Impacts American Attitudes on Climate and Environmental Policy | PRRI,” October 4, 2023. https://www.prri.org/research/the-faith-factor-in-climate-change-how-religion-impacts-american-attitudes-on-climate-and-environmental-policy/. 43% of religiously unaffiliated respondents say that climate change is a crisis, while only 8% of white evangelicals and 10-31% of all other Christian categories agreed.

[v] Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) conducts extensive research into public opinions on a variety of social issues, segmented by religious affiliation and practice, race, and other factors. In addition to climate change opinions, White evangelicals consistently score the lowest in regard to matters of public concern including Christian nationalism: https://www.prri.org/press-release/survey-two-thirds-of-white-evangelicals-most-republicans-sympathetic-to-christian-nationalism/ , structural racism: https://www.prri.org/research/creating-more-inclusive-public-spaces-structural-racism-confederate-memorials-and-building-for-the-future/ , and immigration: https://www.prri.org/spotlight/evangelicals-and-immigration-a-sea-change-in-the-making/; see also https://www.prri.org/research/immigration-after-trump-what-would-immigration-policy-that-followed-american-public-opinion-look-like/.

[vi] Prominent among these are Harper, Kyle. The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire, The Princeton History of the Ancient World. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2017, documenting the role of the Roman Climate Optimum beginning in 3rd century BCE in the rise of the Roman Empire, and the Late Antique Little Ice Age of the 6th and 7th centuries CE in its decline and fall; Jenkins, Philip. Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith: How Changes in Climate Drive Religious Upheaval. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021, examining the religious consequences and persecution of religious minorities that accompanied severe climate-driven shocks: and Parker, Geoffrey. Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013, focusing on the General Crisis of the mid-17th century brought on by failed harvests and famine due to declines in the solar sunspot cycle; and Anderson, Robert Warren, Noel D. Johnson, and Mark Koyama. “Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100–1800.” The Economic Journal 127, no. 602 (June 1, 2017): 924–58, correlating the persecutions of Jewish minorities in Europe with decreasing growing-season temperatures.

[vii] Jenkins, Philip. Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith: How Changes in Climate Drive Religious Upheaval. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021, 5.

[viii] Ibid., 11.

[ix] Griswold, Eliza. The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches from the Fault Line between Christianity and Islam. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010, 9-10.

[x] Jenkins, Climate, Catastrophe, 2.

[xi] Koyama, Kōsuke. Mount Fuji and Mount Sinai: A Critique of Idols. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1985, 242.

[xii] Uchimura, Kanzo, cited in Mouw, Richard J. The Suffering and Victorious Christ: Toward a More Compassionate Christology. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2013, 2-3.

[xiii] Kitamori, Kazō. Theology of the Pain of God. Richmond: John Knox Press, 1965, 128-136.

[xiv] The apophatic or negative propositions are drawn from the following sources: Hall, Douglas John. Lighten Our Darkness: Toward an Indigenous Theology of the Cross. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976. Hall, Douglas John. The Cross in Our Context: Jesus and the Suffering World. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003. Hall, Douglas John. What Christianity Is Not: An Exercise in “Negative” Theology. Cascade Books, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2013. The Christian Century. “Cross and Context,” October 13, 2010. https://www.christiancentury.org/article/2010-08/cross-and-context.