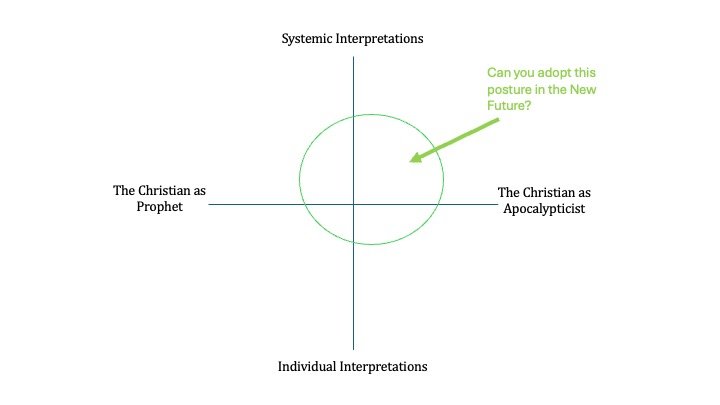

We would like to propose a new conceptual graph to augment the one we have used in Pre-Consultation papers 1-4. This graph is an effort to visualize our responses in the New Future in terms of the personal v. systemic, and in terms of the prophetic v. apocalyptic.

We encourage those who are challenging Old Future understandings to do more than just become prophets, but also apocalypticists,[i] and then commit to work for systemic interpretations and change, not just individual or personal ones.

This second graph owes much to Wes Jackson and Robert Jensen’s book An Inconvenient Apocalypse: Environmental Collapse, Climate Crisis, and the Fate of Humanity (Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 2022). This short book was recommended reading after Pre-Consultation paper #1 and we again commend it to you, including Chapter Three: “We Are All Apocalyptic Now.” In turn, many of you will recognize Jackson and Jensen’s use of theologian Walter Brueggemann’s framework whereby the prevailing “royal consciousness” is challenged by the “prophetic imagination.”

Why apocalyptic, more than prophetic? The prophetic voice demands justice and righteousness, assuming that justice can actually be attained given wise and righteous choices. But Jackson and Jensen pose this challenge:

Invoking the prophetic… implies that a disastrous course can be corrected. But what if the justification for such hope evaporates? When prophetic warnings have been ignored, time and time again, what comes next? That is when an apocalyptic sensibility is needed. The shift from the prophetic to the apocalyptic can instead mark the point when hope for meaningful change within existing systems is no longer possible and we must think in dramatically new ways. Invoking the apocalyptic recognizes the end of something. It’s not about rapture but a rupture severe enough to change the nature of the whole game (108).

Foregrounding an apocalyptic sensibility vis-à-vis a prophetic one accomplishes two things. First, it encourages a more honest accounting about the dimension of the crisis and the extent of the costs involved. Second, it loosens the grip upon us and our communities of current economic, cultural and religious systems with their false claims of being inevitable, irreplaceable, and unchallengeable. We are declaring, in effect, that we have lost hope in a world governed by systems for which few can today imagine alternatives.

And why systemic, more than personal? For decades now, Creation Care activists have focused on the individual, calling Christians to recognize the scriptural mandate to care for God’s world. In effect, we have been trying to “save the world without really changing anything” (other than ourselves). But we have learned the folly of hoping against hope that our economic, political, international and religious institutions will actually act in ways that are contrary to much of their inherent logic.

Jackson and Jensen write:

We are apocalyptic; we think modern systems are coming to an end, and we need to lift the veil that obscures an honest assessment of what those end times will require of us. Along with any individual and community action, a larger political process is necessary to deal with the dramatic changes coming. Being ready for a radically different life for everyone as part of a radically different ecosphere requires planning. Such a process will need to not only build new political and economic systems but also cultivate a more ecological vision to replace the dominant culture’s current linking of a good life to an industrial worldview, what in other writing we have called a “creaturely worldview” (120).

What Jackson and Jensen call the cultivation of “a more ecological vision… [of the] good life. . . [with a] creaturely worldview,” we call “Re-imagined Faith for a New Future,” just some of the very work of our Consultation.

Can you consider with us a migration in the direction of this systemic/apocalyptic quadrant?

[i] For our Consultation, the word “apocalypticist” may be as much a coinage, essentially, as “eco-realism” or “Positive Christianity.” Jackson and Jensen refer to “apocalyptic sensibilities” and both them and we wish to avoid the word “apocalypticism” with all its end-of-the-world baggage. Primarily, if we recognize the prophet (a noun form) as designating a certain type of person who takes a certain posture in society, who fulfills a certain role and undertakes certain projects, then similarly an apocalypticist might find their own unique vocation. Additionally, we might be able to offer “apocalypticist” up against Michael Mann’s accusations against “doomists”. Rather than sit as doomists might—alone and passively—on the Old Future’s ash heap, apocalyptists, in the words of Jackson and Jensen, seek out community, “think in dramatically new ways,” and “stand a better chance of fashioning a sensible path forward” (108, 110).